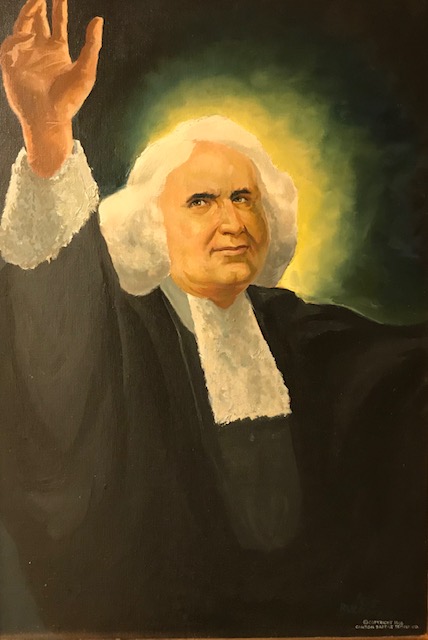

George Whitefield

1714 – 1770

One of the most influential preachers of all time, George Whitefield, the English evangelist, was born in Gloucester, England. He was the son of a saloon operator. His father died two years after George’s birth, and his mother kept the tavern to support the seven small children. George was a real “scamp,” owing to his environmental upbringing. However, he did develop a love for reading and acting plays that contributed to his later success as a great orator. He desired to attend Oxford and did so, working his way through by waiting on tables.

Prior to his conversion Whitefield had several times expressed his desire to become a clergyman. He attempted to please God through his efforts, but would alternate between spells of “saint” and “sinner.” He met the Wesleys, and they became close friends. Because this was previous to John’s own conversion, what they had to offer was strict legalism. He would deny himself all physical comfort by fasting and refusing to do things he enjoyed. After one period of fasting, he physically collapsed, and it was during his recovery that the way of salvation became clear to him. He experienced what he characterized as “joy unspeakable and full of glory.”

Whitefield was ordained a deacon in 1736 and began to preach in jails. Later he did missionary work in the colony of Georgia. He made seven trips to America, where he played an important role in the Great Awakening.

During the early stages of his ministry he was popular, but after arriving back in Great Britain and preaching quite strongly against the drinking and frivolities of that day, he found it increasingly difficult to obtain a pulpit in the established church. This resulted in his turning to the “open-air” meetings which became his trademark. He preached wherever crowds gathered, even at dances and races. The people flocked to hear him. Although he condemned their practices, thousands were converted to Christ. Benjamin Franklin was puzzled over the fact that so many came when they were so plainly condemned for their wickedness.

Whitefield operated the first orphanage in the United States Bethesda, in Georgia. He appealed to crowds on both sides of the Atlantic for its support. Franklin wanted it to be relocated in Philadelphia, and when Whitefield refused, he resolved not to support the work. However, his resolution was not fulfilled as he describes it,

“I had in my pocket a handful of copper money, three or four silver dollars, and five pistoles in gold. As he proceeded I began to soften and concluded to give the copper. Another stroke of his oratory determined me to give the silver; and he finished so admirably that I emptied my pocket wholly into the collection dish, gold and all!”

In 1741 the breach between John Wesley and Whitefield occurred. Whitefield was Calvinist, and Wesley was Arminian. They were reconciled before Whitefield’s death, and Wesley preached a noble memorial sermon for his friend.

His speaking often had remarkable effects upon his audiences. On one occasion, referred to as the Cambuslang Revival, he preached at noon, again at six, and again at nine. At eleven there was a commotion. Conviction seized the sinners, some began weeping. Soon thousands wept, and at times their wails would drown the voice of the preacher. It is said that his voice could be heard for a mile without amplification.

David Hume, the great scientist and philosopher who was not particularly noted for “friendliness” toward evangelical preachers, declared that he would go twenty miles to hear Whitefield. He was indeed a “mighty voice” for thirty-four years of ministry, averaging ten sermons a week. His printed sermons produce some disappointment, being detached from the man. On a balcony not far from his deathbed, he preached his last message to more than two thousand people and died within an hour after extending the invitation to the lost to repent and receive Christ.